Life and Ideas

Through a poverty-stricken and persecuted life Thomas Spence stuck to his 'Plan' for a free and equal world. He spenthis days in London from 1792 carting his pamphlets about for sale and providing a focal point for anyone with a dislike of aristocrats, landlords, the exploitation of children and oppression of all kinds. His is a story of radicalism from below.

Thomas Spence was a self-taught militant who believed that the land had been stolen from the people and should be returned to them. This idea was the corner stone of his Plan

NEWS FLASH! For new research on Spence's life and the significance of his brother take a look at Graham Seaman articles (2018) at the bottom of this page

Spence's Plan

1. the end of aristocracy and landlords;

2. all land should be publicly owned by 'democratic parishes', which should be largely self-governing;

3. rents of land in parishes to be shared equally amongst parishioners;

4. universal suffrage (including female suffrage) at both parish level and through a system of deputies elected by parishes to a national senate; *

5. a 'social guarantee' extended to provide income for those unable to work;

6. the 'rights of infants' to be free from abuse and poverty.

*Although Spence's notion of suffrage was universal (both men and women) he held that women should not be allowed to stand for national office or other 'public employment' (see, for example, 'The Constitution of Spensonia' on this site)

Spence's Rights of Man

Spence may have been the first English person to speak of 'the rights of man'. The following recollection, composed in the third person, was written by Spence while he was in prison in London in 1794 on a charge of High Treason. Spence was, he wrote,

the first, who as far as he knows, made use of the phrase "RIGHTS OF MAN", which was on the following remarkable occasion: A man who had been a farmer, and also a miner, and who had been ill-used by his landlords, dug a cave for himself by the seaside, at Marsdon Rocks, between Shields and Sunderland, about the year 1780, and the singularity of such a habitation, exciting the curiosity of many to pay him a visit; our authorw as one of that number. Exulting in the idea of a human being, who had bravely emancipated himself from the iron fangs of aristocracy, to live free from impost, he wrote extempore with chaulk above the fire place of this free man, the following lines:

Ye landlords vile, whose man's peace mar,

Come levy rents here if you can;

Your stewards and lawyers I defy,

And live with all the RIGHTS OF MAN

The cave where Spence chalked these words was dug out by 'Jack the Blaster'. It is now a pub called the Marsden Grotto Restaurant which offers 'delicious Gastropub food and will appeal to young or old with a love of the almost mythical maritime history of the Grotto, captured perfectly by the decor'. Anyway if you go into the back cave you will see an old fireplace (on the east wall, behind one of the tables). This fireplace is propably a mid-Victorian addition but it is of the sort that Spence would have seen on his visit. The cave has an entry on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marsden_Grotto

Spence's Rights of Infants

Spence's angry defense of the rights of children has lost little of its potency. It is Spence at his best: furious and taking on the world. When The Rights of Infants was published in 1796 it was way ahead of its time. Perhaps it still is. Spence's essay also expresses a clear committment to the rights of women (although he appears unaware of Mary Wollstonecraft's 1792 Vindication of the Rights of Women, which responded to Thomas Paine's Rights of Man, 1791).

Spence's Ideas Catch On

To be a revolutionary in the early decades of the ninteenth century England was to be a Spencean. Despite their humble, 'street-level' origins, Spence's ideas caught on. A report issued by a Government Secret Committee of 1817 noted that

'the doctrines of the Spencean clubs have been widely diffused through the country either by extension of similar societies or by missionaries.'

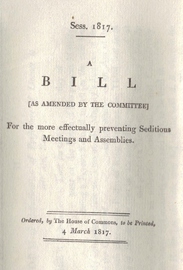

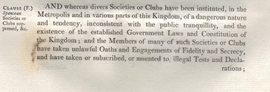

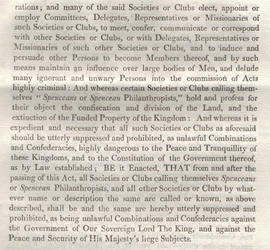

The influence of Spence (even after his death) was taken so seriously that in the same year, 1817, being a Spencean was made illegal. You can find an image of the original Parliamentary Bill banning ‘All societies or clubs calling themselves Spencean or Spencean Philanthropists’ at the bottom of this page.

It is perhaps even more notable that, well after his death, support for Spence's far-reaching radicalism was chalked up by ordinary people on walls:

'We have all seen for years past written on the walls in and near London these words 'Spence's Plan' (Letter from William Cobbett to Henry Hunt)

'His disciples chalked the words ['Spence's Plan'] on every wall in London.' (Letter fromT.J. Evans to Francis Place)

A 1807 poem by 'Mr Porter', included in Spence's Songs of the same year runs:

SPENCE'S PLAN By Mr Porter

As I went forth one Morn /For some Recreation, /My thoughts did quickly turn, /Upon a Reformation, /But far I had not gone, /Or could my thoughts recall, sir, /Ere I spied Spence's Plan /Wrote up against a wall sir.

I star'd with open Eyes, /And wonder'd what it meant sir, /But found with great surprise /As farther on I went, sir, /Dispute it if you can, /I spied within a Lane sir, /Spence's Rights of Man, /Wrote boldly up again sir.

Determin'd in my mind, /For to read his Plan, sir, /I quickly went to find /This enterprising man, sir, /To the Swan I took my flight, /Down in New-Street-Square sir, /Where every Monday night, /Friend Tommy Spence comes there sir.

I purchased there a book, /And by the powers above sir, /When in it I did look, /I quickly did approve sir.

The diffusion of Spencean ideas amongst the social elite was minimal. He had almost no contact with such circles. But amongst many ordinary people his 'Plan' was important and articulated a profound political yearning. In 1817 Thomas Malthus observed that,

It is also generally known that an idea has lately prevailed among the lower classes of society that the land is the people's farm, the rent of which ought to be divided equally among them ; and that they have been deprived of the benefits which belong to them, from this their natural inheritance, and by the injustice and oppression of their stewards, the landlords.

Spence's Life

Spence's activities, especially in London, were under continual surveillance and harassment. He was beaten up more than once and his bookshops attacked and plastered with 'warning' notices by the authorities or loyalist groups. The charge of 'seditious libel' arose from Spence's selling of pamphlets, either his own or Paine's Rights of Man . The following is a pretty thin list and may contain mistakes. It leaves out Spence's central role in radical groups such as the London Corresponding Society.

1750 June 21st, born, Quayside, Newcastle

1775 lecture to The Philosophical Society, Newcastle, later published as 'The Rights of Man'

1776 -1779 teacher at Free Grammar School, Haydon Bridge

1779 -1787 teacher at Sandgate Chapel School, Quayside, Newcastle

1781 married Miss Elliott in Haydon Bridge, son William born

1787 (or 1788?) moved to London

1792 set up bookstall in Chancery Lane

1792 arrested for seditious libel

1792 imprisoned for short period

1793 opens bookshop 'The Hive of Liberty' in Holborn

1793 arrested for seditious libel

1793 Pigs' Meat (Spence's penny weekly) first appears

sometime before 1794 married again, his first wife having died sometime between 1781-1792

1794 arrested for High Treason

1794 imprisoned for 7 months without trial (charge of High Treason)

1797 son William dies

1797 moves to 9 Oxford Street

1798 arrested on suspicion of inolvement with United Irishmen

1801 arrested and imprisoned for one year (seditious libel)

1814 died

1815 Society of Spencean Philanthropists formed

1817 Spencean clubs and socities made illegal

Portraits of Spence

Spence was one of 19 children. His mother, Margaret Flet, sold stockings, his father was a netmaker. Spence was an odd, difficult, utterly sincere man. A contemporary of Spence, Francis Place, described him as follows:

he was a very simple, very honest, single-minded man ... he loved mankind and firmly believed that the time would come when it would be wise, virtuous and happy.

He was perfectly sincere, unpractised in the ways of the world to an extent few could imagine in a man who had been pushed about in it as he had been. Yet what is still more remarkable, his character never changed, and he died as much of a child in some respects as he probably was when he arrived at the usual age of mankind.

He . . . was querulous in his disposition and odd in his manners, he was remarkably irritable and seemed as if he had always been so, his disposition was strongly marked in his countenance, which marked him as a man soured by adverse circumstances and at enmity with the world. ... In person he was short, not more [than] five feet high, he was small and had the appearance of feebleness at an age when most men still retain their vigour, this was however partly occasioned by a stroke of palsy from which he never entirely recovered. His face was thin and much wrinkled, his mouth was large and uneven, he had a strong northern ' burr' in his throat and a slight impediment in his speech. His garments were generally old and sometimes ragged ... he had not, therefore, many points of attraction.

Another contemporary, William Hone, had this to say of Spence:

Spence was a native of Newcastle, small in stature, of grave countenance and deportment, serious in speech and with a broad burr in his accent. He would sometimes relax at little evening parties where his plan was discussed. On these occasions he sang a song highly characteristic of himself and his plan, in which is a sentiment denoting the pleasing state of being "free as a cat" and indeed his love of personal independence was as great as any Man's, or greater, with a fierce impatience of oppression and rigidly pertinacious of his plan, which was ever first in his thoughts and foremost in his purpose, it is not surprising that in his humble walk in life he lived with difficulty and died poor, leaving nothing to his friends but an injunction to promote his "Plan" and the remembrance of his inflexible integrity.

William Cobbett was present at Spence's trial for seditious libel in 1801 (Spence received a one year sentence). In later life, when Spence's name had become venerated amongst radicals, Cobbett recalled:

I was present in the Court of King's Bench. He [Spence] had no counsel but defended himself and insisted that his views were pure and benevolent, in proof of which, in spite of all exhortations to the contrary, he read his pamphlet through. He was found guilty and sentenced to be imprisoned for I forget how long. He was a plain, unaffected, inoffensive looking creature. He did not seem at all afraid of any punishment, and appeared much more anxious about the success of his plan than about the preservation of his life. After he came out of prison, he pursued the inculcation of his plan, appearing to have no other care; and this he did, I am assured, to the day of his death, always having been a most virtuous and inoffensive man, and always very much beloved by those who knew him.

Cato Street

The Cato Street Conspiracy occured seven years after the death of Spence and is further evidence of his significant influence in radical circles. It was undertaken by the group known as the Society of Spencean Philanthropists. The Cato Street Conspirators were arrested on February 23rd 1820 and executed on 1 May. This was for their part in the ‘West End Job,’ an attempt to assassinate the British Prime Minister and his cabinet.

For more information see:

https://www.catostreetconspiracy.org.uk/people/thomas-spence

The script reads:

I AMONG SLAVES ENJOY MY FREEDOM 1796

Spence's New Script and Pronunciation System

Spence was a self-taught radical with a deep regard for education as a means to liberation. He pioneered a phonetic script and pronunciation system designed to allow people to learn reading and pronunciation at the same time. He believed that if the correct pronunciation was visible in the spelling, everyone would pronounce English correctly, and the class distinctions carried by language would cease. This would bring a time of equality, peace and plenty: the millennium. He published the first English dictionary with pronunciations (1775) and made phonetic versions of many of his pamphlets. A page from one of these pamphlets can be seen at the end of our page dedicated to Spence's 'Utopias'

In Spence's system Newcastle become Nuk'as'il, whilst his title 'The Restorer of Society to its Natural State', becomes 'Dhe Restorr ov Sosiete tu its nateural Stat'.

see the 'English/Tokens' page and the bibliography for more details

Spence's Coins

Spence's name is well-known amongst coin collectors. This would have pleased him. Spence used his tokens to distribute his ideas and was so fond of them that his friends thought it fit to bury him with a couple of his favorites (including one called 'the Cat': remember Hone's account of Spence: 'He would sometimes relax at little evening parties where his plan was discussed. On these occasions he sang a song highly characteristic of himself and his plan, in which is a sentiment denoting the pleasing state of being "free as a cat"').

Spence wrote a work on coin collecting in 1795 (The Coin Collector's Companion). This has now been re-issued (Gale ECCO print editions) and is available on Amazon.

I'm no expert in coins but from what I understand Spence issued three types: a) existing coins countermarked with radical phrases, for example 'War is starvation' and 'Full bellies, fat bairns' (a unique collection of these is shown on this site; see English/Tokens page); b) new coins, or tokens, with a political intent. The most common of these advertise Spence's penny weekly Pigs' Meat;c) tokens issued for the use of others, such as Spence's brother. A few coins are shown below and others throughout these pages. Spence's tokens have survived in greater numbers than Spence's orginal written works and are regularly sold by coin dealers.

Spence's tokens need to be seen as part of wider late eighteenth century fashion for using coins to advertise almost anything, including political convictions. In his Companion he notes the 'universal rage of collecting coins'.Whether worn around the neck (well I am guessing so since they sometimes have holes at the top), collected or passed about as substitute coinage, there were many radical coins (such as the tokens announcing the acquittal for High Treason of London Corresponding Society activist Thomas Hardy) and anti-revolutionary ones.

The best overview of the coins can be found at:

http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/dept/coins/exhibitions/spence/index.html

A clear and useful recent (2007) academic article by John Barrell with good quality images of Spence's coins and lots of contemporary reports (about half way through the article) of their reception (pretty mixed) can be found at:http://www.erudit.org/revue/ron/2007/v/n46/016131ar.html

--------------------

BELOW:

script: 'MAN OVER MAN HE MADE NOT LORD'

'PIGS MEAT PUBLISHED BY T. SPENCE LONDON'

Anti-Spencean Satire

It is a testament to the influence of Spence that his work and his followers provoked, not just Government legislation to suppressSpencean activity, but also lively satire. The picture below is from the front cover of Radical State Papers (1820). This work claims tobe a compilation of State Papers from 'the Spencean Commonwealth' and takes readers through the advent and demise of an eccentric - what might be satirised today as 'loony left' - Spencean state. One can get a flavour of its contents by looking at the proposed Spencean 'Bill of Rights' (proposed under the new revolutionary calendar, in the month of Capricorn, Year 2 of the Spencean Revolution):

1. No Spencean shall wear clean linen; dirt covers a multitude of skins.

2. Premiums shall be given for burglary; no Spencean shall be obstructed in his calling on the highway.

3. Property is common; there shall be no palings nor walls.

4. Women are common - there shall be no monopoly

The print shows, far right on the platform, a Napoleon pig figure, a personification of Pigs' Meat; to its right stands a personification of the most popular radical newspaper of the time, Black Dwarf. In the middle we have 'Orator Hunt'. In front we have a grotesque rabble, 'the swinish multitude'.

Poem and Song by Keith Armstrong

(Keith Armstrong is a contemporary North East poet and founder of The Thomas Spence Trust)

(AFTER THE NAME OF THOMAS SPENCE’S BOOKSHOP AT 8 LITTLE TURNSTILE, HOLBORN)

The Law Against Spenceans

Thomas Spence's family life - three puzzles

by Graham Seaman

Introduction

Fifteen years after Thomas Spence's death, Francis Place tried to collect the materials for a biography. The materials were sparse. Thomas Spence himself was scrupulous in avoiding any mixing of family and political affairs, and in all his writings there are just two references to his early life: one mentioning the poverty of his family and his numerous siblings; the other, that he and his brothers were taught to read and discuss the Bible with their father while working. The engraver Thomas Bewick, who was a personal friend, included a few paragraphs of biography and some anecdotes in his own memoirs (not seen by Place). Thomas Evans, who was a close collaborator with Spence in London wrote a brief summary of Spence's political life with almost no personal contents. The most detailed account comes from Eneas Mackenzie, topographer and historian, whose parents, like Spence's father, had migrated from Aberdeen to Newcastle. Mackenzie was born in 1778 ([Rudkin] p.34), and so was only a child while Thomas Spence was still in Newcastle. However, Mackenzie not only read Spence's works, but also had local sources of information.

For all biographers after Evans, Mackenzie became the main source of information. Even though Francis Place had known Spence in the London Corresponding Society in the

1790s, he knew almost nothing of his personal history, and his own notes begin Mr Mackenzie in his Memoir of Thomas Spence says …

([Place] p.141).

But Mackenzie's account is still brief and unconfirmed by other sources. Place grumbled that:

The publications in which any thing is related of his birth education progress in life and opinions are as might be expected few, short, and unsatisfactory and but little has been gleaned from persons who knew him in the later years of his life, notwithstanding much pains have been taken to procure information. ([Place] p.155)

He began to send off letters to possible friends of friends in Newcastle: "I am particularly desirous to learn all I possibly can respecting Mr. Spence's early life, his parents and his brothers and sisters." It appears that no reply came back. And so things have stayed for the last 150 years. The few original sources have been embellished over time, sometimes from new but unconfirmed sources and sometimes by pure guesswork, but the fundamental framework for Spence's life remains the notes of Mackenzie. The two established twentieth century biographies are [Rudkin] and [Ashraf], both of whome inevitably based their accounts largely on these same few sources, though Ashraf made more use of contemporary official documents.

The increasing availability of eighteenth century records, especially newspapers and church records, has begun to change this situation. First copied to microfiche from the 70s on, then digitized, and finally transcribed, this has made it much simpler to find and access data which can confirm or refute the received story. To a growing extent this also allows missing details to be filled in. However, there are two major limitations to the process. Firstly, any stage in the sequence from photography to transcription may be incomplete. It is easy to assume that data which cannot be found never existed and come to false negative conclusions. Contrariwise, as many church records simply consist of a name and a date, it is easy to assume that any reference to a particular name is a reference to the person of interest and come to false positive conclusions. There were, for example, at least four different individuals named 'Thomas Spence' active in Newcastle in the second half of the eighteenth century. It may never be known exactly which individual some records refer to.

Eneas Mackenzie's account of Spence's early life in Newcastle ([Mackenzie2]) is short enough that it is worth repeating entire (omitting descriptions of his ideas and publications):

Mr. Thomas Spence … was an elder brother of Jeremiah Spence. Their father came to Newcastle from Aberdeen about the year 1739, and, after following his business as a net-maker for a few years, opened a booth upon the Sandhill, for the sale of hardware goods. He was twice married and had nineteen children. His second wife, Margaret Flet, a native of the Orkneys, was an industrious woman and kept a booth for the sale of stockings. She was the mother of Thomas, who was born on the Quayside, June 21, 1750. …

He learned his father's trade, but did not long pursue it. While a youth, he became clerk to Mr. Hedley, a respectable smith on the North Shore. After this he opened a school in Peacock's entry, on the Quayside. He was also a teacher in St. Ann's school, at the east end of Sandgate, and, for a short while, had an engagement at Haydon Bridge school. … While at Haydon Bridge, he married a Miss Elliot, of Hexham, by whom he had one son …

Mr. Spence it seems was not very happy in his selection of a wife, which combined with a desire of propagating his system more extensively, induced him to leave Newcastle, and to settle in London …

… His first wife, who had kept a shop in King St, died in the north, revious to his second marriage.

One of Spence's sisters, now the wife of Joseph Glendinning, tailor, of this town, had, by her first husband, a son, named John Gibson, who died at Liverpool on January 20, 1810, aged 22 years, and who was a very ingenious and promising young man …

Mackenzie's knowledge of Spence's background in Newcastle depends on details not recorded in any existing printed works, and so appears more grounded in local information than his knowledge of Spence's life in London, which is largely based on evidence Mackenzie takes from the fly-sheets of Spence's own publications.

In regard to his family, Mackenzie's assumption was that Mr. Jeremiah Spence, slopseller, a man of most distinguished worth

, would be better known to citizens

of Newcastle than Thomas. His mention of only three siblings from the nineteen he claims suggests that the rest were unknown to him, whether because they lived obscure lives or because they stayed

behind in Aberdeen where he had no sources.

Validating Mackenzie: Jeremiah and Mrs. Gibson

A simple first step is to check whether the contemporary documentation for Thomas's siblings matches Mackenzie's account. Jeremiah is the most straightforward, but not even he is fully documented. 'Jeremiah Spence' is not a unique name, and there was more than one present in Newcastle in the late 18th century[2]. The principal facts given by Mackenzie are:

- He was Thomas's younger brother, so born after 1750

- He was a slop-seller by trade (a seller of seamen's tackle)

- His shop was in the Sandhill in Newcastle. This was a square close to the quayside which was also home to the Exchange and Guildhall

- He was a follower of the Reverend Murray (in the High Bridge Meeting House) and after his death in 1782 became a Glasite and attended the Glasite Forster Street Meeting House, where he was the leading member (the Glasites attempted to minimize any formal hierarchy).[1]

His connection with Thomas is itself only partly confirmed by his authorship of verses On Reading the History of Crusonia, signed 'J.S' in the phonetic

edition of the History (J.S. could equally well be 'James Spence', or even 'Joseph Smith'), but more definitely by the tokens struck for J. Spence, Slopseller, Newcastle

with the edge legend

SPENCE DEALER IN COINS LONDON

. Of course, neither of these shows him to have been Thomas's brother rather than having some other connection, but at this point Mackenzie's evidence really

becomes conclusive.

The Newcastle Courant of 8/11/1794 announced that an office and ware-room situate on the south-east corner of the Sandhill in Newcastle, in the occupation of Mr

Jeremiah Spence, [et al]

were to be sold by private contract. So it seems likely that Thomas' and Jeremiah's father's booth upon the Sandhill for the sale of hardware goods

mentioned by

Mackenzie was inherited by Jeremiah.

Jeremiah died in November 1803, aged 43, placing his birth in 1760 and making him 10 years younger than Thomas. The obituary in the Newcastle Courant read simply:

Wednesday last, aged 43, Mr Jeremiah Spence of this town, slop-seller, much respected

.

There is no online record of his baptism in Newcastle (as will be seen, this becomes a recurrent theme). But on 19/11/1782 a Jeremiah Spence married Mary Whitaker, both of the St. Nicholas chapelry (St. Nicholas was the grandest church in the city, almost directly behind the Sandhill). Both signed their names fluently. If this is our Jeremiah, then although he would then have been worshipping at the Forster Street Meeting, marriages were required by law to take place in an Anglican church such as St. Nicholas'[3]. The signature on the marriage certificate is clear and simple copperplate without any strongly distinguishing features, but it does match the signature on 'Jeremiah's plan' [4].

There are no digitised baptismal records for any of Jeremiah and Mary's children (the Forster Street Meeting House records do not seem to have survived). A Jeremiah Spence who might possibly have been their son was was buried in the Newcastle Ballast Hills graveyard in 1791. However, a William Whittaker Spence, Newcastle shopkeeper, must surely be theirs, and is documented by his marriage, the baptisms of his children, in the 1835 Poll Book, and in later censuses. William Whittaker Spence married a Margaret Reid on 21/4/1808, and their first son, baptised in 1810, was named Jeremiah (Jeremiah died in infancy but their fourth son was given the same name). Discounting the first Jeremiah, the couple had 3 daughters and 5 sons: surely enough to have left at least one descendant with an interest in genealogy who may have found out more about their ancestors.

So although there is no absolute confirmation of Mackenzie's description of Jeremiah and his relationship with Thomas, the outlines of his story can be expanded with some degree of confidence.

What about the other sibling, wife to Mr. Gibson and Joseph Glendinning, and mother of future poet John Gibson? A Mary Gibson married Joseph Glendinnen [sic] on 21/11/1796 in St. John's, Newcastle. Further confirmation comes from the baptism of their sons, James and Jeremiah in 1798, where her maiden name is given: Mary Spence. Mary's marriage to Mr Gibson is harder to trace: the only candidate I have found is the marriage of a Mary Spence to William Gibson in St James, Westminster, in 1785, where both are 'of this parish'.

If this is the right couple, then this suggests an early connection of the Spence family with London[5], though of course 'Mary Spence' is quite a common name. It was not uncommon in the period for well-off couples to travel to a larger town or city for their wedding, implying that if this is them, William must have been consderably richer than Mary, And indeed a William Gibson, shipwright, and his wife Mary, had their son John Gibson baptized in All Saints, Newcastle, on 31st August 1788, matching the age of 22 at death in 1810 given by Mackenzie. I have not found records of William, John, or Mary's burial. All the same, although some of this evidence is circumstantial, the essentials match well with Mackenzie.

Puzzle One: Thomas's Birth Family

Which means we should give considerable credence to Mackenzie's story of the arrival of Thomas's father from Aberdeen in 1739, his second marriage to Margaret Flet, from the Orkneys, and the nineteen siblings from the two marriages (of whom only three are so far accounted for). However, none of this has been documented anywhere except by Mackenzie, as Place discovered.

Flet was indeed a common name in the Orkneys at the time, and there were several Margaret Flets born in the right period. Newcastle church records in turn give the marriage of a William Spence, pedlar, to Margaret Flat [sic], spinster, in All Saints Church (at the back of the Quayside), on 25th July 1749. 'Pedlar' is perhaps not so far from 'having a booth on the Sandhill', though it might imply a degree more mobility. The marriage date is a conventional and respectable one year before the birth of Thomas, making him their oldest son. Thomas's own son was in turn called William, as was Jeremiah's: naming after the paternal grandfather being a convention of the time.[6]

Thomas himself confirms that his parents had a large family, mentioning the many difficulties my poor parents met with in providing for, and endeavouring to bring

up their numerous family decently and creditably

([Conversation]). But neither Thomas nor

Mackenzie says anything about William's first wife or whether his children with her stayed behind in Aberdeen or travelled with him. So there are 16 children left to find.

On William's arrival in Newcastle he would have joined an already large Scottish migrant community - including other families named Spence - based around Sandgate and the Quay. These migrants were members of the Scottish Presbyterian church, not the Church of England, and if dissenters, they were dissenters from the Scottish church, with their own breakaway sects. We already know that Jeremiah was a member of the Scottish Glasite sect, and that he and Thomas were inspired by the Presbyterian Reverend Murray, so it seems that in this aspect this Spence family was quite typical. This means that although their marriages (like William and Margaret's) would be registered in Anglican churches, as required by law, their baptisms would probably be in Presbyterian chapels.

The Presbyterian chapels in general kept good records, anxious to show that they were within the law. The records for the majority of these chapels listed by Mackenzie in the 1820s have survived, at least partially. This includes Garth's Head chapel, St James Meeting House, Carlise Street Chapel, Wall Knoll Chapel, the High Bridge Meeting House, and the Groat Market Meeting House. It does not include the Forster Street Meeting House, where Jeremiah worshipped (unless the Forster Street records have been preserved under another name). The Garth's Head records date back to 1708, the Groat Market Meeting House's records to 1715, and the St James's chapel records to 1746. All the other chapels were founded rather later, although Mackenzie says that Wall Knoll (which has records only from 1781) was the descendant of earlier, less formally organized, meeting houses in the Sandgate [7]. Any records of William and Margaret's children are therefore likely to be found in these three chapels, if anywhere.

However, there are no baptisms for Thomas, Jeremiah, or Mary to be found online around Newcastle. There are three baptisms of Thomas Spences close to the birth date given by Mackenzie - 21st June 1750 - including one, baseborn son of a father also called Thomas, only a week later on 1st July 1750. But the father clearly married his partner after this, having 7 more children together, and turns out to have been a barber living in North Shields. The other two Thomas Spences registered in Groat Market Meeting House are sons of a David Spence, born in 1752 and 1754 respectively (clearly the first-born died in infancy). Similarly for Mary - there are Mary Spences baptised in the right period, but all can be eliminated as having other parents[8]. And there are no Jeremiahs baptised around 1760 at all, nor are there any other children of William and Margaret Spence. The reluctant conclusion has to be that all their children were baptised in one of the predecessors of the Wall Knoll Meeting for which records have not survived.

This means that any other children of William and Margaret will only be identified through later life events, perhaps by assembling trees for all the Spences in Newcastle at the time, and identifying unknowns. This would not be easy. Another possibility would be to find them through burial records.

Presbyterian burials in Newcastle did not usually take place in the chapel grounds (if any), but in the Ballast Hills. Mackenzie wrote:

The probability is, that these hills, or wastes, were used by the earliest Scottish emigrants as a place for burying their dead; for the old, stern, unbending Presbyterians, considered the very entrance into an episcopal church as an overt act of idolatry, and would by no means suffer the funeral service to be read over their dead. This burial place was formerly much larger; for houses have been built, and glass-house cinders poured over the graves of many who had been interred without the present enclosed ground. It does not appear that any enclosure was made until the year 1785. Mackenzie, p. 408

The burial records for the Ballast Hills survive, and have been available in print for many years. However, they are incomplete and patchy, especially for the earlier

period. Willam and Margaret's burials are likely to be found here, if anywhere. And indeed there is a record in the Ballast Hills Register: Margaret Spence, buried 23/5/1797

. Is this Margaret

Flet? There is no record for William, but there is a record for George Spence son of William Spence, died December 21 1751 aged only 15 months. Born in October 1750, this would clash with our

Thomas's birth, so the father must be a different William: and in fact he turns out to be the son of a William and Isobel Spence, whose children were baptised in St James' Chapel.

Tracing any possible children of William Spence from his first marriage is necessarily even harder: would they have been born in Aberdeen or Newcastle? What was his

first wife's name? There are no large Spence families recorded in Aberdeen, though there are several William Spences in the area each with two or three children. There is a family of the right date

in Orkney, with 9 recorded children to a William Spence baptised between 1726 and 1737. But it would be a complete guess to associate any of them with William Spence, pedlar, of Newcastle, formerly

of Aberdeen. It seems that Thomas's family of birth is still nearly as shrouded in mystery as it was when Francis Place wrote: Except someone would, which I can hardly expect any one will, hunt

out his relatives and take some particulars from their mouths, I can't expect to learn much.

([Place]

p. 325)

Puzzle Two: Miss Elliot

According to both Mackenzie and Thomas Bewick's memoirs, Thomas Spence taught a school in the Broad-garth, Newcastle — afterwards taught writing and arithmetic etc

in the great school at Heydon Bridge and lastly he was master of St Ann's public school in Sandgate

([Bewick] p. 73).

Mackenzie also says that while Spence was teaching at Haydon Bridge, west of Newcastle, he married a Miss Elliot of Hexham.

Place has more unanswered questions for his Newcastle contact ([Place] p.328):

- Who was Miss Elliot

- How Spence and his wife procured their maintenance

- Whether she came to London with him

- The time when he came to London

- What business she followed after she was separated from her husband

- Where and how she died

Some, but not all of these questions can now be answered.

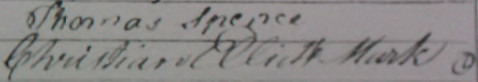

Thomas Spence's marriage is recorded in the Hexham church register: Thomas Spence of the Chapelry of Haydon and Christian Elliot of this parish were married by

banns on the 6th October 1777

. Thomas signed his own name, while Christian gave only her mark - the letter 'C'. Thomas's signature is his usual one: a small flourish on the crossbar of the T, but

otherwise plain copperplate. The witnesses were Stephen Bewick (not a relation of Thomas Bewick's as far as I can tell - another branch of Bewicks were well established in Hexham) and the

churchwarden.

Christian Elliot was baptised by her father John Elliot, a labourer, in Hexham on 28th January 1756, making Christian 21 to Thomas's 27 [9]. Christian was the youngest of four daughters, Dorothy, Mary and Margaret, with one younger brother John. Their father John was probably born in Hexham in 1716, son of William Elliot and brother to Robert, Matthew, and William.

Christian moved to Newcastle with Thomas, and their only son, William, was born on July 26th 1781 and baptised in the High Bridge Meeting House by the Reverend Murray himself on 12th August. The chapel had been founded by supporters of the Reverend Murray in 1764; but William's baptism was almost the last he carried out before becoming too ill to practise, after which, according to Mackenzie, Jeremiah (and presumably any others of William's children) moved away from the chapel. William is the only Spence in the High Bridge records.

Three years after their son's birth, the Newcastle and Gateshead Directory [Whitehead] showed two entries for Thomas Spence:

Spence Tho. school-master, St Ann's school.

Spence Tho. grocer and tea-dealer, King-street.

The first is definitely 'our' Thomas. The second might be. Where the register shows other couples running different businesses, the husband is given his first name and the wife is simply 'Mrs'. But the fact that Mackenzie records Christian as running a shop in King Street may clinch it.

Thomas continued to teach until 1787. Ashraf ([Ashraf] p. 15) says that the Common Council minutes record Thomas Spence leaving St. Ann's school on 17/12/1787. Almost simultaneously (7/12/1787) an advertisement appears in the Newcastle Courant for 'Spence's Registry Office', an employment agency for servants being run from a T.Spence's toyshop in Pudding Chair (now Pudding Chare, and site of the Groat Meeting House). While not provable, it seems likely that Spence was at this point supporting himself on two businesses: this one, and Christian's shop in King St.

At some point following this the relationship between Thomas and Christian broke down and on an unknown date he made his way to London together with their son William. According to Mackenzie, Christian remained behind with her shop.

Mackenzie wrote that He was not very happy in his selection of a wife, which, combined with a desire of propagating his system more intensively, induced him to

leave Newcastle, and to settle in London

.

Evans on the other hand wrote that Spence was persecuted after publishing his paper to the Philosophical Society, and children withdrawn from his school, leading him to flee Newcastle [8].

None of this seemed quite a specific enough reason to leave a steady income for an unknown future in London, either to Rudkin, who suggested the driving reason could have been the death of one of Thomas's publishers, Thomas Saint, or to Ashraf, who implied that Thomas might have lost his job due to a stroke.

What neither Rudkin nor Ashraff had seen was the manuscript of Thomas Bewick's memoir. The published version was edited by his daughter Jane, who left everything in

Bewick's account of Thomas Spence untouched apart from one sentence, which she deleted: At this time [when Thomas was master at St Ann's] his wife kept a shop in the Black Gate, and by her

mismanagement, Spence (who was a careful sober man) failed and was led into great difficulties - on which account he gave up St Ann's School, and went to London.

King Street is at the back of the Quayside, while the Black Gate is 10 minutes walk away and Pudding Chare another 5 minutes beyond that. These are definitely three different shops. Perhaps Mrs Spence had taken on new premises between 1784 and 1787, and this was the cause of the bankruptcy. But why did Bewick's daughter suppress any mention of the problem?

One possibility is that Christian Elliot herself may have been a bit too close to Jane Bewick for comfort. In 1786, Thomas Bewick married Isabella Elliot. Isabella Elliot was the daughter of a farmer, Robert Elliot, of Ovingham. She had played with Thomas Bewick as a child, but was actually born in Woodgate on the southern bank of the Tyne. We already know that Christian had an uncle Robert, but it seems unlikely that it was this Robert. Still, even if Christian and Isabella were not first cousins, they may have been closely enough related for Jane to want to spare her mother's family embarassment (or she may simply have felt that her father was taking Thomas Spence's side against Christian).

The last of Place's questions about Christian is 'where and how she died'. By the time of his second marriage in September 1791 Thomas is 'a widower', so Christian died between 1787 and 1791. Mackenzie certainly says that she stayed behind to run the King St shop and "died in the North". There is no record currently to be found for the burial of a Christian Spence in Northumberland (though it is quite likely she would have had a pauper's unmarked grave in the Ballast Hills). But there is one tantalizing hint: the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, has a record of a Christian Spence of Shoe Lane workhouse being buried on 4/6/1790. Is it possible that Christian did follow Thomas to London, in such dire straits as to need the workhouse for a time? How far had their income collapsed before Thomas eventually found the funds to run his street bookstall sometime around 1791?

Puzzle 3: Thomas and Ann

It seems certain that by the end Thomas and Christian did not get on. Davenport, writing from memory many years later, said So much was she the termagant, that he

[ie. Thomas] often compared himself to Socrates, who was cursed during his life with the scolding Xantippe!

([Davenport] p. 2)

But his relationship with his second wife seems much more complex, having turned itself into a commonplace of gossip among his acquaintances: a source of pity or mockery among those who saw him as a simple eccentric; and a sign of nobility of character among his supporters.

Mackenzie gives the longest version of the story. His source was clearly among the mockers:

In the article of female beauty, Mr Spence was a connoisseur. One morning, in passing along one of the streets of London, with a parcel of numbers, he perceived a very pretty girl cleaning the steps of a gentleman's house. He stopped, looked at her, and then enquired if she felt disposed to marry. On the maid answering in the affirmative, he offered himself, was accepted, and married the same day. But neither was this marriage a happy one. The girl, who had married him merely to be revenged on her sweetheart, with whom she had quarrelled, soon repented, and lavished her attentions upon her first lover. She afterwards went to the West-Indies with a sea-captain; yet, on her return, Spence pardoned her transgressions, and restored her to favour. But the safety of his health and property compelled him, at length, to dismiss her from his house; though he allowed her 8s. per week during his life.

Place, reading this, wrote: In p.9 Mr Mackenzie gives a note of Mr. Spence's second marriage. I wish very much for more particulars or references. I can learn

nothing here respecting her nor can I trace the woman.

This time he had a little more luck. Part of the story was confirmed by two of his unnamed respondents, both clearly sympathizers. Both confirmed that she had run away

to North America with another man, been abandoned by him, and returned to Spence who had taken her back. Both also stated that this had happened after his first arrest

, one saying in

1794

, and one under what is popularly called the Suspension of Habeas Corpus Act

. One of the two adds that Spence took her on again to his bosom, till she died

, which conflicts with

Mackenzie's (more detailed) version.

Either way, the impression given by the gossip is of an unworldly man marrying a woman who has no interest in him, and who suffers her to mistreat him, whether as a saint or a fool. There are a few hints that this may not be entirely the case.

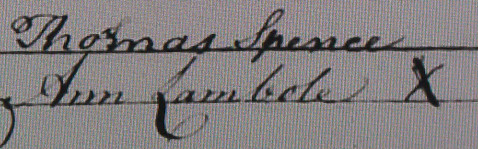

The marriage took place in St. Leonards, Shoreditch, on 9th September, 1791. Thomas was described as "Thomas Spence, widower of this parish" and the bride, Ann Lambole, as "spinster of this parish". The witnesses were a Henry Sparrow and the churchwarden. Thomas signed with his usual clear but simple signature; Ann, with an X only[10]. The marriage was by banns, where the announcement has to be made once a week for three weeks before the wedding - designed to allow for any change of mind by the couple, and not quite the rushed affair Mackenzie implies.

I can find no further trace of Ann in church records. Lambole is a name mostly restricted to the south of England, with several variant spellings (Lambold, Lamboll, etc), and although there is at least one Ann Lambole of a suitable age born in Hampshire (born in Kingsclere in April 1755) there were also Lamboles already living in London.

But there is one last trace in the newspapers. Both Place's informants give the timing of her desertion as 'after the first arrest'. They agree that this was 1794, or at the time of the suspension of Habeas Corpus. That was not actually Spence's first arrest, but his second; the first arrest and trial ran over the whole year 1792-3. So Ann must have stood by him throughout this. Spence's second arrest, in which he was charged with high treason, and during which Habeas Corpus was suspended, saw him in Newgate prison from May to December 1794. The Morning Post of May 21st recounted:

Mr Spence, Bookseller, of Little Turnstile, was yesterday taken into custody by the Bow-street Runners, attended by a Messenger. Spence would have made his escape, as he got on the outside of the house, but for the information given by one of his neighbours. His wife behaved with infinite resolution; after the Runners had put the husband into a coach, they were returning to seize his books, but were prevented by Mrs Spence, who shut the door, and desired them if they dare to break open the house like house-breakers.

This does not sound like the behaviour of someone who does not care about her husband, or at least her husband's work. During the following seven months, the wives of the London Corresponding Society members accused of treason were subsidized by the LCS, Mrs. Spence among them. William, then 12, was briefly held for helping to sell Spence's "Rights of Man in verse", after which he was presumably looked after by Ann for the seven month duration of Spence's imprisonment. So it was after this, or towards the end of this time, that Ann left with her 'paramour' for Jamaica. The last record of William is in 1796 when he drew an illustration for The Reign of Felicity, which appeared in both print form and on a token.

After this all we have are Mackenzie's statements that William 'died young', and that after Ann's return she was eventually evicted but paid maintenance till Spence died; or alternatively, Place's anonymous informant's statement that Ann died before Spence. At this date burial records of the poor are still rather patchy, and fewer are on-line than baptisms and marriages, so it is possible that more concrete information may yet emerge. All we can do for now is search for deaths of 'William Spence' and 'Ann Spence', and hope that there is something more than a name and a date. There is indeed an Ann Spence buried in St. Saviours, Southwark, in 1798, at age 36 (so 12 years younger than Thomas). If this is her, then Mackenzie is right that Thomas had evicted her, and she had moved south of the Thames. Given the early date (4 years to pack in travel to Jamaica, return, forgiveness, and expulsion) it seems possible but unlikely. There is also a William Spence resident at 7 Newcastle St (near Fleet Street), buried 24th October 1819, at the right age - 38. But Mackenzie would hardly have counted this as 'died young'. It seems likely that all we can hope for in both cases is a greater degree of plausibility rather than proof.

In which case there are also Thomas's own works to consider. Firstly, his written works: the fourth letter in the Restorer of Society is on the right to divorce, introduced in France during the Revolution ([Restorer], Letter 4). Not surprisingly, he is in favour. The argument is studiedly impersonal, but the conclusion is not: "This subject is so feelingly understood in this Country, that it is supposed the chains of Hymen would be among the first that would be broken, in case of a Revolution, and the family business of life turned over to Cupid, who though he may be a little whimsical, is not so stern, and Jailor-like a deity". This does not sound like a person disillusioned by love.

Secondly, his tokens. Some of these are purely commercial; many relate to his written works, while others make political statements he could not dare to put in

writing. But there is a residue of tokens resistant to any other interpretation than the personal. There is one of this category which was struck in far greater numbers than any of his other tokens,

with the exception of the 'Pig's Meat' advertisements: this has Thomas Spence's head on the obverse with the legend 7 months imprisoned for High Treason

and the date 1794 (not the year of

striking, which was probably later), and on the reverse a heart in an open palm under the single word 'Honour'. Nowadays a symbol of the American Shakers (or of charity in general), and once a symbol

of the Oddfellows, what did it mean to Spence? Could it have been a message to Ann?[11]

Thomas Spence himself died in London on September 8, 1814, age 57. His burial is duely and tersely noted in the records of St. James, Westminster.

Conclusions

We now know more details of the lives of Thomas's siblings, Jeremiah and Mary, and the name of his father. We know more about his first wife and at least the probable name of his second wife. But the first of Place's puzzles - the details of his family of origin - is still a mystery. Perhaps more details will be filled in over time as more records become searchable (or local historians find better ways to approach the data), or perhaps his numerous family are condemned forever to the invisibility which has nearly always been the fate of the poor. Thomas himself was the proof that this invisibility can be overcome without betrayal or desertion.

Footnotes

[1] Mackenzie comments:

The Glassites, having dissented from the Church of Scotland, are mostly descended from Scottish parents. This small community has existed in this town for nearly 70 years. Amongst its most zealous members were the late Mr. Leighton, surgeon, and subsequently Mr. Jeremiah Spence, slop-seller, a man of the most distinguished worth. He and a few others, who had belonged to the Rev. James Murray's congregation, joined the Glassites. as being the most exempted from, what they conceived to be, the unscriptural aristocracy of religion.

[2] 'Jeremiah Spence' is an unusual name but not a unique one. A Jeremiah Spence, son of Jeremiah Spence, was baptised in Alnwick, to the north of Newcastle and site of the Rev. Murray's original ministry, in 1764. His grandfather was also Jeremiah, so this was a family tradition. There were Jeremiah Spences in Berwick upon Tweed and the Orkneys, too. So the mere name 'Jeremiah Spence', while not common, is not on its own enough to identify Jeremiah Spence, the slop-seller and Glasite (and presumed brother of Thomas).

[3] Oddly, the same marriage is also recorded in summary form in St. Andrew's church, where the record says simply: "19th November 1782: Jeremiah Spence and Mary Whitaker, spinster".

[4] Jeremiah wrote a response to a Government inquiry on the cost of grain in 1801. This included what he called his own 'plan' for reform. See http://somewhere.

[5] Another unprovable hint that this might be the case is the record of a James Spence, slop-seller, insuring his premises in Wapping with the Sun insurance company in 1790 [London Metropolitan Archives MS 11936/366/566063]. Might this be another brother, following in Jeremiah's footsteps?

[6] Ashraf assumed that Thomas's father was called Jeremiah ([Ashraf] p. 11). I do not know why she made this assumption.

The suburb of Sandgate has long been the favourite resort of poor and industrious adventurers from Scotland, on their first arrival. This people, being deeply embued with the spirit of religion, seem to have opened several places of worship in this neighbourhood early in the last century (Garth Heads Presbyterian Meeting-house). A Presbyterian congregation met in a place in Sandgate still called "the Meeting-house Entry." … The present meeting house was finished in 1765.

[8] In particular, there is a baptism of a Mary daughter of William Spence in St John's Church, Newcastle, on 1/2/1758; but this seems likely to have been a different William Spence, born in Morpeth.

[9] A second Christian Elliot married a James Smith (both 'of this parish') by banns in Hexham on 29/8/1773. But it is not likely that she was the daughter of John Elliot: at age 17 she would have to have been married by license from her parents, not by public banns. There is no record of another Christian Elliot being baptised in Hexham; however, a Christian Elliot was baptised 22/5/1748 in All Saints Church in Newcastle, daughter of Robert Elliot, a smith. This Christian would have been a more suitable age for marriage to James Smith, and John Elliot had a brother named Robert.

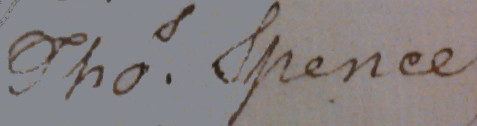

[10] Since there is no other evidence that Thomas's wife was Ann Lambole, or that he had any connection with Shoreditch, while there were two other Spence families using St. Leonards in the late 1780s to 90s, everything rests on the details of the certificate. The date is possible (though earlier than generally supposed; Thomas was generally believed to have come to London in 1792, though not based on any definite evidence). The status as widower is also correct. Both of these are circumstantial; the claim depends fundamentally on the signature, which resembles other examples of his signature but is unfortunately rather plain. [EDITOR'S NOTE: IMAGES OF THE THREE SIGNATURES ARE SHOWN AT THE END OF THIS ARTICLE]

[11] There is another more mundane possibility: that this was one of a small series of tokens celebrating public houses, particularly those where the LCS used to meet. One of these was the Friend in Hand, but Heart in Hand is also not an uncommon name for a pub, and many 18th century pubs have disappeared without trace. But if so, why the single word heading 'Honour'?

References

- [Ashraf] P.M. Ashraf, The Life and Times of Thomas Spence, Gateshead 1983

- [Ballast] Ballast Hill Cemetery Register, Newcastle on Tyne Record Series, Vol IX Miscellanea

- [Bewick] Thomas Bewick, My Life, ed. Ian Bain, Folio Society, London 1981

- [Davenport] Allen Davenport, The Life, Writings and Principles of Thomas Spence, London 1836

- [Evans] Thomas Evans,A Brief Sketch of the Life of Mr Thomas Spence, Manchester 1821

- [Mackenzie] Eneas Mackenzie, A descriptive and historical account of the town and county of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle 1827, online at The Internet Archive

- [Mackenzie2] Eneas Mackenzie, Memoir of Thomas Spence of Newcastle upon Tyne, from Mackenzie's History of Newcastle, Newcastle 1826

- [Newcastle] Newcastle Magazine Number 3, January 1821, Thomas Spence, in Notices of Local Biography

- [Place] Francis Place, Collection For a Memoir of Thomas Spence and the Spenceans, 1830-31, unpublished manuscript. British Library Add. Mss. 27808

- [Rudkin] Olive D. Rudkin, Thomas Spence and His Connections, New York 1927

- [Restorer] Thomas Spence, The Restorer of Society, London, 1801, online at Marxists Internet Archive

- [Conversation] Thomas Spence, An Interesting Conversation, London, 1794, online at Marxists Internet Archive

- [Whitehead] William Whitehead, The Newcastle and Gateshead directory for 1782 - 4, Newcastle 1784, online at University of Michigan

© Graham Seaman 2018. Made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Jeremiah Spence's Plan

Graham Seaman

Introduction

Jeremiah Spence was Thomas Spence's younger brother, born ten years after Thomas in 1760. Like Thomas, he was strongly influenced by the Rev. James Murray's radical social and religious teachings. Unlike Thomas, he remained all his life in Newcastle, expanding their father's shop into a business selling seaman's kit with offices and warehouse in Sandhill in Newcastle, and after the Rev. Murray's death in 1782, becoming a leading figure in the Glasite Forster Street Meeting House. He died at the age of 43 in 1803, a respected figure in the Newcastle religious and commercial scenes.

There is one published piece of political writing assumed to be by Jeremiah, a poem attached to Thomas Spence's early utopian work ‘The History of Crusonia’ from 1783 entitled ‘On reading the History of Crusonia’[1], and signed ‘J.S’. If ‘J.S.’ is indeed Jeremiah then at age 23 Jeremiah may not have been much of a poet but was happy to be publcly seen to be sympathetic to Thomas's ideas. What was not known was to what extent he kept this sympathy into later life. He must certainly have stayed on reasonable personal terms with his brother until the mid 1790s, when Thomas had an advertising token struck for ‘J. Spence, Slop-seller, Newcastle’ [2]. But there is no preserved record of communication between them during Thomas's periods of imprisonment, when he was rather desperately appealing to others for financial help, even to buy food.

So it is surprising to learn that there is an unpublished political work by Jeremiah, which he goes as far as to call his ‘plan’ which is couched in quite angry and radical terms; but which is quite different in contents from Thomas's plan.

A series of increases in the price of flour and staple grains which had been disastrous for the poor led to Parliamentary inquiries in 1799 and 1800. The inquiry published a first report in February 1800 and a follow-up in March. Subsequently the Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland, initiated a survey of the state of the market in corn, by sending a printed questionnaire to be distributed among parishes across England for responses by the clergy. The questionnaire was intended to elicit detailed statistics on the production and prices of corn in each area relative to other crops.

Jeremiah responded to reports of the Home Secretary's investigations with a letter and an attached ‘plan’. Both are preserved with the responses to the questionnaire, all sent around the 6th of November 1800, in the National Archives (HO/42/53/63). From the wording of Jeremiah's letter it appears he had not seen the questionnaire itself.

Jeremiah's letter flatly negates the premise of the investigation, stating that there is no shortage of corn; that the problem is not in production but in the market, which is being manipulated by speculators — and that Parliament's own reports are encouraging market prices to settle at levels that assume a shortage. The general argument was not unusual on the left: Thomas, for example, had reprinted an anonymous pamphlet ‘The Rights of Swine’ as long before as 1794, which asked:

Why is it then, that while there is plenty of bread the poor are starving? Is there not as much grain and grass in the land as when the trade flourished?

But this area was not Thomas's speciality; he does not seem to have had any detailed knowledge of or interest in the actual operations of the market. His own diagnoses of the financial problem were rather vague condemnations of “the taxes and the paper money, which now enhance the price of everything” (Restorer of Society, Letter 11) and he assumed that the market traders, following implementation of the Spencean plan, would “immediately enter into a competition with each other striving who should first lower their articles till everything found the lowest level” (ibid.). Why this would not also apply to wages is not clear, and nor is why external market-influencing disasters would stop: Thomas simply assumes that he can keep the good side of the market without its bad side.

Jeremiah's letter is polite; obsequious, almost. Jeremiah's ‘plan’, however, is more in the style of a draft for a pamphlet, not written specifically to send to his Grace, but used opportunistically. It is actually several plans, with rather oddly different levels of ambition and detail. The first is to use the law to limit speculation in grain in the same way that profits on money-lending were limited by having a fixed interest rate, or that bakers' profits were legally fixed so that bread prices could not diverge too greatly from the price of wheat. In a sense this is a more realistic position than Thomas's: it is not possible simply to have the good side of a free market without the bad, so it must be limited by law if the risk of starvation is to be avoided. Jeremiah is also aware that the problem does not start with the market speculators, but with farmers who face the temptation to hoard their grain to force the selling price up. Again, he suggests a legal remedy: inspection of farm grain stores by government Commissioners, reminiscent to us of Russia in 1928.

The second plan, covered in a single short paragraph, is to limit the size of farms:

The restricting the Number of Acres to be held by Farmers, by diminishing the Quantity in each Hand, would greatly increase the Care in Cultivation, and consequently the Produce.

This idea was already supported by Murray, and was a commonplace among radicals since much earlier in the century. But this time it is Thomas with the greater realism:

The unprecedented dearness of provisions sets every head on devising how to find a remedy. And as people impute much of the mischief to the manner gentlemen now follow of letting their lands in large farms, they talk of having laws made to reduce farms again to a moderate size. But this is reckoning without their host. This is like the mice tying a bell about the cat's neck. Whose to do it? Are not our legislators all landlords?

It is childish therefore to expect ever to see small farms again, or ever to see anything else than the utmost screwing and grinding of the poor, till you quite overturn the present system of landed property.

Restorer of Society, Letter 5, Sep 20th 1800

Which does seem a very valid objection to all of Jeremiah's proposals to make use of the law to solve the pricing problem.

The third and last plan from Jeremiah is to trade the public right to access foothpaths across farms — which reduce the total land area available for cultivation — for an obligation on the farmer to maintain a smaller number of cart roads. This restriction of a common right goes completely agains the grain of Thomas's thought, and the history of more recent struggles for the right to roam makes it hard for a modern audience to sympathize with the idea.

The text is signed by Jeremiah personally, and gives no indication of his church office, which he presumably would have had to have had to be officially asked for an opinion. This is consistent both with the Glasite's deliberate lack of hierarchical structure, and Jeremiah's known prominence in the Glasite Forster Street Meeting House in Newcastle. But it is equally possible that he simply sent in his letter and plans unsolicited on the date of the official inquiry.

In conclusion: While Jeremiah and Thomas's common background in radical protestantism and concern for the public good are at the heart of the letter and plan, Jeremiah's writing is clearly influenced by his roles as businessman (in his concern for the effect of wage rises on international competivity), ratepayer (in his concern for the costs of road maintenance), and believer in the aristocracy. It is not influenced by his brother's work, whether because he was unaware of it or because he disagreed with it. Perhaps if they had been able to work together, Jeremiah's business experience might have led Thomas to be more aware of the growing importance of the market as an independent phenomenon — Jeremiah playing Engels to Thomas's Marx — or perhaps they would have ended at cudgels with one another. We shall never know.

Jeremiah's Letter

His Grace the Duke of Portland

May it please your Lordship

It was with infinite concern and regret I saw the publication of Your Grace's Ideas concerning the Quantum of Corn in the Country, in Your Letter addressed to the Lord Levitt of Nottinghamshire. Well knowing the Effects such a resport must produce, for, it is well remembered by the poorer part of the Community, and those concerned with them, that the price of Grain was Moderate untill the enquiry was set on Foot by Order of Parliament early in last Year, when on the respost of Scarcity being spread abroad an instant advance in price took place on every sort of Corn and Flour, and which has continued ever since to the great distress, nay almost entire starvation of the lower Orders of the people.

I do not mean in answering this Tract[?], to charge the Parliament then nor your Grace now with any intention to injure the Public but much the contrary, and I should be sorry to shew my Opinion in the way I am now doing in a public manner; but, judging it to be the Duty of every Loyal Subject to do all he can for the good of Society, I beg your Graces attention to the matters I have taken the liberty to lay before You — And I now beg leave to add that the Effect of Your Grace's opinion being made public (that a scarcity does exist) has again raised the price of Grain both at Home and abroad — for from a Letter from Hamburg it appears this report has raised the price of Grain there also.

One thing that may lead Men unskilled in judging of unthreshed Corn to conclude there is a want in this years produce, is, the small quantity of Straw attached to it this year which makes so much difference at [sic] that of One half in point of Bulk — I mean that on an average, One Stack of Corn this year contains as much Grain as two of the same Bulk last year, and of a far superior Quality altho‘ it does not fill the Eye in the same proportion.

The interest also which Farmers and Corn-dealers have in supporting the Idea of scarcity may naturally lead them to withhold a true and fair account of what stock is in the Country and therefore I have thought that the Respectable Gentlemen now called upon to Act as Commissioners under the Income Act might (under the Authority of Government) form a proper Channel for obtaining a satisfactory statement from every Farmer put upon Oath before them, what quantity of Corn they really suppose they have in their possession.

I have heard it candidly asserted by very Judicious Men here in the Farming line that an average Crop when sold in the proportion of 12/- per Winchester Boll for wheat would enable them to pay their Rent and every expence attendant on their Business and leave them a fair reasonable profit — Now admitting this and that this years Crop has even faild a full Quarter part — even in this View 16/- per Boll, holds the same proportion, and with some advantage to the Farmer, who has less to Reap, thrash, and sell, yet produces the same Sum of Money for it — Now how unfair is it then for the People to pay nearly double the latter Sum for that Articule, which is exacted from them without any choice left them, or any means of extricating themselves from the enormous [fran]?? Their daily wants compelling them to give any price demanded for the sustenance of Nature, so true is Solomon's assertion “The Profit of the Earth is for all, even the King is served by the Field” which induces me to inclose a plan for rectifying agreeable to former precedents the Evils complained of.

Jeremiah's Plan

The intolerable Extortions that are practised upon the Public in the Article of Corn cry loudly for Remedy, in order to prevent the ruinous Consequences that must issue should they be continued.

Jealous for the Liberty of the Subject, the Legislature have forborn to enact such Legislation as can always correct this growing evil :- for although the existing Corn Laws in their clear and obvious Tendency, admit the Necessity of preserving a kind of middle Price or Value for Grain, so that when it rises above a certain Price or Value, the Ports are opened, and when depressed below a certain value the Ports are shut. — Yet experience has fully proved the Inadequacy of these Laws to protect the Public from the Power of Corn Dealers in Times of Scarcity who having the Staff of Life in their Possession can compel their Fellow Subjects to pay what Price they please to demand, or can literally starve them to Death in Case of refusal.

Now as the Law ought to protect every Individual, and, if possible, injure none; and in all Cases where this cannot be attained in Perfection, of two Evils to chuse the least. — I mean that Individual Interest should always yield to the public weal. — It must then be admitted, that to attain this valuable End the Legislature would need to make a similar Law to protect the Subject from the Power of the Corn Holder that at present defends the Merchant in Distress against the Avarice of the Monied Man, who might exact, and obtain any Thing he chose to Demand for the Use of this Gold were it not for that salutary Law fixing the Value of Money at 5 per Cent per Annum. — It can be no harder for the Corn Merchant to be confined with respect to his Profits than for the Money Lender as to his. — Or, which still applies more strictly to the Point in Hand, the Baker is obliged by Law to produce his Loaf in Price, Quantity, and Quality, according to the Average Price of Flour from Time to Time, without any scruple.

Now the same Rule, were it applied to the Corn Merchant, would most effectually preserve the People from his imperious Power in all such Times as the present — The average Price of Grain abroad, of every Description, is easily obtained by Government, and also the average Expenses on Shipping, the Freight, Insurance and Delivery at Home,which when ascertained, fixes the average Prime Cost, — and, by allowing him, as in the case of the Money Lender and Baker, a certain per Centage, the Public would enjoy that Protection which Experience has convinced everyone they must need, and are fully entitled to.

By thus fixing the higher Extreme to which imported Grain can rise, the Price of Corn Produce would also be regulated, and that Evil which now threatens the ruin of the Common of the Country. would be corrected, in a great Measure. — For, if the different Articles of Life should hold their present enormous Prices, the Wages of all Sorts of Mechanics must rise in Proportion, and when these are laid upon our Manufactories, they will be so exorbitantly high, that our Merchants will be wholly shut out of the Foreign Markets.

The restricting the Number of Acres to be held by Farmers, by diminishing the Quantity in each Hand, would greatly increase the Care in Cultivation, and consequently the Produce.

Another Plan struck me for the same Purpose which would greatly add to the Quantum of Cultivated Land, and that of the best sort, viz. — If the numerous needless Footpaths through the best and richest Ground in the Country were wholly stopped, and, in Lieu thereof, the Farmer or Land Proprietor be obliged to maintain the Cart Roads through his Grounds in a Capital State of Repair, making & upholding on the most proper Side thereof a good Footpath four Feet broad and nine Inches above the Level of such Road, and also for Pleasure of Passengers take care the Hedges should never exceed four Feet in height above the Level of the Footpath, and this wholly at the Charge of the Farmer or Land Proprietor, relieving the Peasant, who if he has neither Cart nor Horse, can never injure any Road, and therefore in justice should uphold none. — This might be carried into Effect under the Direction of Commissioners for Roads, the same as Highways are regulated, appointed under one general Act for that Purpose.

Your Goodness will excuse the Freedom of my Observations, which, if of any Use in serving the Cause of Humanity will afford me a full Reward:

I am,

Honourable Sir My Lord

With the Greatest Respect & Esteem,

Your Grace's most obt. Humble Servant

Jeremiah Spence

Newcastle 6 Nov 1800

Footnotes

On reading the History of

CRUSONIA

Ho! all ye Tenants, whom Landlords so have press‘d,

Behold the Land where you may be at Rest:

No Tenants are seen there, nor Landlords either,

For Mankind's native Rights will suffer neither.

Hail! Happy Cruson, it only is in thee,

That Men can live in strict Society;

Simplicity the Rule of Heaven's Art,

Thy Constitution reigns through ev'ry Part.

One plain rule does thro' thy Country run,

Each Parish is a Corporation.

To these the Houses and the Land belong,

No curs'd Landlords are suffer'd them among.

Of Rents being rais'd nobody here does fear,

Bidding over others' Heads is needless here.

The Parish Rate is here all that's paid,

And each Man has a vote how that is laid.

This being paid, no Freeholds are so free,

Nor go more surely to Posterity.

Hail! Happy Cruson! there is no praising thee

In aught less than a complete History.

Let then that speak which this wants room to shew,

And let the wretched World thy matchless Fame know.

[2] The claim that Jeremiah struck tokens for Thomas found in [Rudkin] p. 54 and derived from A. Waters' book on Spence is based on a misunderstanding of the date '1775' on the coin: this is the date of Thomas's presentation of his plan to the Newcastle Philosophical Society, when Jeremiah was only 15, not the date the coin was struck. Ashraf claims ([Ashraf]] p. 194) that "several halfpenny and farthing dies made for J. Spence have been described", but I have only been able to trace two: the halfpenny, with a picture of a sailor and the inscription to "J. Spence, slop-seller, Newcastle" on the obverse, and an image of a barge on the "Coaly Tyne" on the reverse; and a similar farthing, which has a similar image of a sailor but the single word "Newcastle".

References

- [Ashraf] P.M. Ashraf, The Life and Times of Thomas Spence, Gateshead 1983

- [Rudkin] Olive D. Rudkin, Thomas Spence and His Connections, New York 1927

- [Thompson] Robert H. Thompson, The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814), British Numismatic Journal 38 (1969) pp. 126-162

- [Waters] Arthur W. Waters, Spence and his Political Works, Leamington Spa 1917

© Graham Seaman 2018. Original content in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

graham@theseamans.net

'Graham Seaman is maintainer of the Spence archive https://www.marxists.org/history/england/britdem/people/spence/ at marxists.org